Friday, August 17, 2007

Another Veil: Europe's Misplaced Fears

Erdogan's AKP (Justice and Development Party) won another resounding victory in July 22nd, against the wishes of Turkey's secularists and the the military establishment. Both had loudly objected to Erdogan's nomination for the post of President of the Republic, with street demonstrations, parliamentary boycotts, and even threats of a military intervention. Erdogan's choice, Abdullah Gul, is one of the most charismatic and well-regarded politicians of the country, but has one main flaw: his wife, Hayrunissa, wears a veil, a piece of clothing banned in government buildings and schools since the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and Mustafa Kemal's westernization of the country in the 1920s. Forced to call early elections, AKP's share of the votes grew from an already generous 34 percent to an unprecedented 47 percent. Short of what would be the fifth military coup in Turkey's volatile democratic history, the Army won't be able to stop Gul's candidacy for President this time around.

Europe, or, more precisely, its Franco-German heart, did not cheer this development. If anything, it gave new vigor to the voices that object to Turkey's admission in the European Union at an uncertain date in the distant future. In the contest for Turkey's soul, it is easier to find Europeans sympathizing with the generals and the secularists than with Erdogan. And it may well be that, at least among policy elites and Eurocrats in Brussels, opposition to Turkey's candidacy stems from the difficulty to absorb 70 million people, many of whom are poor and farmers (how will French farmers survive, mon Dieu)-, but for ordinary Europeans Turkey is just too Muslim. Especially now that it is governed by a hijab-friendly Islamic party and Hayrunissa's veil is just the first step on a slippery slope towards another Green Revolution -this one unrelated to crops.

Here's an Islamic party that won a democratic election by a large margin in 2002, devoted its mandate to bread-and-butter issues, avoided confronting the country's secularism, won re-election by an even larger margin in 2007 after months of protests and veiled threats against it, and re-entered Gul's candidacy to the Presidency with his promises to respect the neutrality of the post and the country's laïcité, and to ask his wife to show a bit more hair. Could you ask for more? Meanwhile, the zealous guardians of Turkey's secularism, are the all-too-powerful military forces, partly responsible for Turkey's harsh limits on freedom of expression, its Armenian-genocide denials, its invasion of Cyprus and subsequent policies vis-a-vis the occupied north of the island, the four military coups interrupting democratically elected governments, and, until recently, its repression of Kurdish rights. If there's anything in Turkey for Europe to fear, it is not the Justice and Development Party.

Similar scenarios appear elsewhere. Many Westerners seem happy to support Fatah -supposedly secularist, but whose gunmen defiantly surrounded the EU office in Gaza and burned flags in the wake of the Danish cartoons' crisis- over Hamas, the winner of a free and fair democratic election in January 2005; happy to condone the repression of Islamist parties by authoritarian regimes in North Africa, from Morocco to Egypt; and terrified by the prospect of elections in Pakistan. In Pakistan, the threat posed by Islamic extremists -dramatically represented by the Red Mosque events- is enough to stall democratic reforms that would most likely benefit the "secular" party of Benazir Bhutto at a moment where the democratic-minded majority has shown how much it cares about the independence of the judiciary. Instead, it is deemed wiser to stick by President Pervez Musharraf, who took power in a military coup, has not fulfilled its promises of democratization, and whose much infamous Inter-Services Intelligence are found to be in bed with every unsavory character on that part of the planet, from the Taliban to Kashmiri jihadis to A. Q. Khan and his nukes-selling bazaar.

In 1991, Europe stood by as the Algerian military canceled the second round of elections after the FIS had won the first one. What followed was a gruesome civil war, among the worst in the century, and a clear sign to many Muslim groups that if they wanted to grab power they had to resort to less civilized means. This is a lesson that should be well learned by now.

Thursday, August 16, 2007

American Income Inequality: Gini in a Bottle

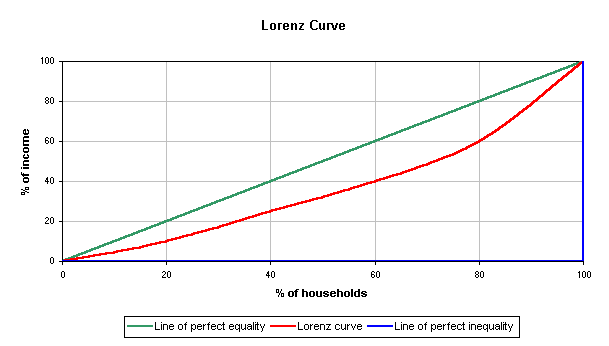

The Gini coefficient is an economic measurement of income inequality in a given society. It’s a number drawn from an economic model called the Lorenz curve, which is a linear representation of the relationship between households and income. In essence, the Lorenz curve is a graph where every point in the curve tells us the answer to the question “what percentage of households have a given percentage of national income”? Above is a good example from Wikipedia.

If income was perfectly even in its distribution, the Lorenze curve would be the green line shown above because there would be a 1:1 ration of households and income (i.e. x=y in that 10 percent of households would have 10 percent of the income, 26 percent of households would have 26 percent of the income, etc). If one person has all the income and no one else has any, than we get the blue line where only the 100th percentile of income earners—this one hypothetical mogul—owns 100 percent of the income.

So the Gini coefficient is a measure of the degree to which the relationship between households and incomes for a given society diverges from the green line (perfect equality) and resembles the blue (perfect inequality). It's calculated thusly:

divided by

the total area of the region below the red line.

The higher this resultant fraction is (so, the bigger the 'distance' between the red line and the green line), the more unequal a society is in terms of income distribution. The US has always had a bigger tolerance for inequality than most other advanced nations (aka has a higher Gini coefficient).

The Gini coefficient has also been steadily rising for thirty years. But it's increase hasn't been even across administrations. From 1993 to 1999, the US Gini coefficient grew by .003, which breaks down to an increase of about .0004 per year. From 2000 to 2005, the Gini coefficient grew by .009--three times as much as in the 1990s.

Let’s say that the Gini coefficient grows at the accelerated rate that it has been since 2000—by .009 every six years. In thirty years, the number would increase by .054, to .523. That would make the

Tuesday, August 7, 2007

Dangerous Propositions: Obama Toughens Up On The "Neglected" Eastern Front

However, he's no dove, and he seems determined to prove it. On the war on terror, on Iran's nuclear weapons' program, and even on Iraq, his positions -laid out in the latest issue of Foreign Affairs- are closer to Clinton than to Kucinich. Following a phony debate with Senator Clinton over hypothetical diplomatic meetings with leaders of "rogue" countries, Obama promised to take the war on terror back to Pakistan and Afghanistan, the "true" front, neglected due to the Iraq diversion. He mentioned he would redeploy some of the troops being pulled out of Iraq into Afghanistan, where the Taliban and Al-Qaeda are experiencing a resurgence and seem, according to the National Intelligence Estimate, stronger than ever since Operation Enduring Freedom in 2001. In addition, faced with evidence of Taliban regrouping in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas and the North West Frontier Province of Pakistan, Senator Obama said the following: "There are terrorists holed up in those mountains who murdered 3,000 Americans. They are plotting to strike again. It was a terrible mistake to fail to act when we had a chance to take out an al-Qa'eda leadership meeting in 2005. If we have actionable intelligence about high-value terrorist targets and President Musharraf won't act, we will."

These comments were received with criticism by most pundits and presidential candidates, on both sides of the political spectrum. The exceptions are notable: Rudy Giuliani and Hillary Clinton, who again outdid Obama in hawkishness by maintaining that in such a hypothetical, nuclear weapons should not be taken off the table. Despite the pundits' criticism, it is hard to imagine that the general public in the United States would oppose such a move. For all the "invasion fatigue," few expect Americans to react negatively against limited attacks on Al-Qaeda bases, regardless of sovereignty issues or Pakistani protests. After all, did anyone object -or even care- about the United States' intervention in Somalia only a few months ago? Obama's comments appeared on the heels of revelations that military bureaucracy had averted plans to use Special Ops against Al-Qaeda leadership -al-Zawahiri included- in Pakistan in 2005, in a similar fashion to Clinton's frustrated plans to take on Osama Bin Laden in 1998.

The problem is not how would Americans react to such a decision, but how would Pakistanis and the Muslim world in general. In Afghanistan, as in Iraq, more troops do not guarantee victory. The Brits doubled up their military engagement in Helmand province and since then the situation has only worsened. For all the talk of rebuilding the country, the only Americans or NATO soldiers that typical Afghans outside Kabul encounter are the ones that eradicate their year-long harvest of poppy crop or fly the planes that wipe out entire families of innocent civilians along with militants. As in the Cold War, containment, rather than rollback or appeasement, is the better policy. Taliban control of the southern provinces will likely ebb and flow, but they cannot take over Kabul like they did in 1996.

But the real issue is Pakistan. Although not treated as such, Pakistan is the key country in the so-called war on terror. It is the second most populous Muslim country and its nuclear arsenal counts with more than 100 warheads. It is a battleground where Islamic radicalism and secular democratic forces fight daily for the heart of the country. In Pakistan, as far as the United States is concerned, less is more. When the United States invaded Afghanistan in 2001, the Islamists were the direct beneficiaries in the following elections, gaining twice as many votes as they previously had and catapulting them into positions of power in the North West Province and Baluchistan. As General Musharraf struggles to handle multiple challenges to his rule, from both secular and religious forces, and Pakistan toys with democracy in moments of uncertainty, it is not difficult to imagine how tough talk of US intervention would strengthen the Islamists and more radical groups over the secular forces expected to group around Benazir Bhutto. It seems like an awful price to pay for a few terrorists on the loose.