Friday, August 17, 2007

Another Veil: Europe's Misplaced Fears

Erdogan's AKP (Justice and Development Party) won another resounding victory in July 22nd, against the wishes of Turkey's secularists and the the military establishment. Both had loudly objected to Erdogan's nomination for the post of President of the Republic, with street demonstrations, parliamentary boycotts, and even threats of a military intervention. Erdogan's choice, Abdullah Gul, is one of the most charismatic and well-regarded politicians of the country, but has one main flaw: his wife, Hayrunissa, wears a veil, a piece of clothing banned in government buildings and schools since the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and Mustafa Kemal's westernization of the country in the 1920s. Forced to call early elections, AKP's share of the votes grew from an already generous 34 percent to an unprecedented 47 percent. Short of what would be the fifth military coup in Turkey's volatile democratic history, the Army won't be able to stop Gul's candidacy for President this time around.

Europe, or, more precisely, its Franco-German heart, did not cheer this development. If anything, it gave new vigor to the voices that object to Turkey's admission in the European Union at an uncertain date in the distant future. In the contest for Turkey's soul, it is easier to find Europeans sympathizing with the generals and the secularists than with Erdogan. And it may well be that, at least among policy elites and Eurocrats in Brussels, opposition to Turkey's candidacy stems from the difficulty to absorb 70 million people, many of whom are poor and farmers (how will French farmers survive, mon Dieu)-, but for ordinary Europeans Turkey is just too Muslim. Especially now that it is governed by a hijab-friendly Islamic party and Hayrunissa's veil is just the first step on a slippery slope towards another Green Revolution -this one unrelated to crops.

Here's an Islamic party that won a democratic election by a large margin in 2002, devoted its mandate to bread-and-butter issues, avoided confronting the country's secularism, won re-election by an even larger margin in 2007 after months of protests and veiled threats against it, and re-entered Gul's candidacy to the Presidency with his promises to respect the neutrality of the post and the country's laïcité, and to ask his wife to show a bit more hair. Could you ask for more? Meanwhile, the zealous guardians of Turkey's secularism, are the all-too-powerful military forces, partly responsible for Turkey's harsh limits on freedom of expression, its Armenian-genocide denials, its invasion of Cyprus and subsequent policies vis-a-vis the occupied north of the island, the four military coups interrupting democratically elected governments, and, until recently, its repression of Kurdish rights. If there's anything in Turkey for Europe to fear, it is not the Justice and Development Party.

Similar scenarios appear elsewhere. Many Westerners seem happy to support Fatah -supposedly secularist, but whose gunmen defiantly surrounded the EU office in Gaza and burned flags in the wake of the Danish cartoons' crisis- over Hamas, the winner of a free and fair democratic election in January 2005; happy to condone the repression of Islamist parties by authoritarian regimes in North Africa, from Morocco to Egypt; and terrified by the prospect of elections in Pakistan. In Pakistan, the threat posed by Islamic extremists -dramatically represented by the Red Mosque events- is enough to stall democratic reforms that would most likely benefit the "secular" party of Benazir Bhutto at a moment where the democratic-minded majority has shown how much it cares about the independence of the judiciary. Instead, it is deemed wiser to stick by President Pervez Musharraf, who took power in a military coup, has not fulfilled its promises of democratization, and whose much infamous Inter-Services Intelligence are found to be in bed with every unsavory character on that part of the planet, from the Taliban to Kashmiri jihadis to A. Q. Khan and his nukes-selling bazaar.

In 1991, Europe stood by as the Algerian military canceled the second round of elections after the FIS had won the first one. What followed was a gruesome civil war, among the worst in the century, and a clear sign to many Muslim groups that if they wanted to grab power they had to resort to less civilized means. This is a lesson that should be well learned by now.

Thursday, August 16, 2007

American Income Inequality: Gini in a Bottle

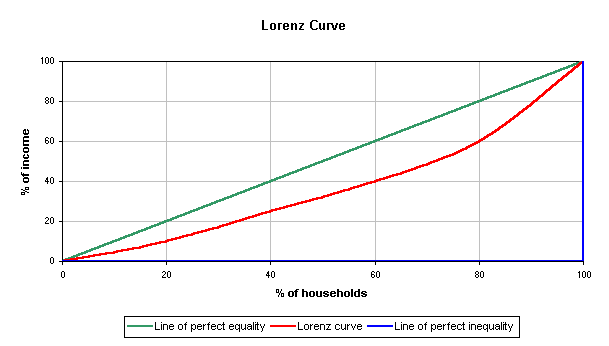

The Gini coefficient is an economic measurement of income inequality in a given society. It’s a number drawn from an economic model called the Lorenz curve, which is a linear representation of the relationship between households and income. In essence, the Lorenz curve is a graph where every point in the curve tells us the answer to the question “what percentage of households have a given percentage of national income”? Above is a good example from Wikipedia.

If income was perfectly even in its distribution, the Lorenze curve would be the green line shown above because there would be a 1:1 ration of households and income (i.e. x=y in that 10 percent of households would have 10 percent of the income, 26 percent of households would have 26 percent of the income, etc). If one person has all the income and no one else has any, than we get the blue line where only the 100th percentile of income earners—this one hypothetical mogul—owns 100 percent of the income.

So the Gini coefficient is a measure of the degree to which the relationship between households and incomes for a given society diverges from the green line (perfect equality) and resembles the blue (perfect inequality). It's calculated thusly:

divided by

the total area of the region below the red line.

The higher this resultant fraction is (so, the bigger the 'distance' between the red line and the green line), the more unequal a society is in terms of income distribution. The US has always had a bigger tolerance for inequality than most other advanced nations (aka has a higher Gini coefficient).

The Gini coefficient has also been steadily rising for thirty years. But it's increase hasn't been even across administrations. From 1993 to 1999, the US Gini coefficient grew by .003, which breaks down to an increase of about .0004 per year. From 2000 to 2005, the Gini coefficient grew by .009--three times as much as in the 1990s.

Let’s say that the Gini coefficient grows at the accelerated rate that it has been since 2000—by .009 every six years. In thirty years, the number would increase by .054, to .523. That would make the

Tuesday, August 7, 2007

Dangerous Propositions: Obama Toughens Up On The "Neglected" Eastern Front

However, he's no dove, and he seems determined to prove it. On the war on terror, on Iran's nuclear weapons' program, and even on Iraq, his positions -laid out in the latest issue of Foreign Affairs- are closer to Clinton than to Kucinich. Following a phony debate with Senator Clinton over hypothetical diplomatic meetings with leaders of "rogue" countries, Obama promised to take the war on terror back to Pakistan and Afghanistan, the "true" front, neglected due to the Iraq diversion. He mentioned he would redeploy some of the troops being pulled out of Iraq into Afghanistan, where the Taliban and Al-Qaeda are experiencing a resurgence and seem, according to the National Intelligence Estimate, stronger than ever since Operation Enduring Freedom in 2001. In addition, faced with evidence of Taliban regrouping in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas and the North West Frontier Province of Pakistan, Senator Obama said the following: "There are terrorists holed up in those mountains who murdered 3,000 Americans. They are plotting to strike again. It was a terrible mistake to fail to act when we had a chance to take out an al-Qa'eda leadership meeting in 2005. If we have actionable intelligence about high-value terrorist targets and President Musharraf won't act, we will."

These comments were received with criticism by most pundits and presidential candidates, on both sides of the political spectrum. The exceptions are notable: Rudy Giuliani and Hillary Clinton, who again outdid Obama in hawkishness by maintaining that in such a hypothetical, nuclear weapons should not be taken off the table. Despite the pundits' criticism, it is hard to imagine that the general public in the United States would oppose such a move. For all the "invasion fatigue," few expect Americans to react negatively against limited attacks on Al-Qaeda bases, regardless of sovereignty issues or Pakistani protests. After all, did anyone object -or even care- about the United States' intervention in Somalia only a few months ago? Obama's comments appeared on the heels of revelations that military bureaucracy had averted plans to use Special Ops against Al-Qaeda leadership -al-Zawahiri included- in Pakistan in 2005, in a similar fashion to Clinton's frustrated plans to take on Osama Bin Laden in 1998.

The problem is not how would Americans react to such a decision, but how would Pakistanis and the Muslim world in general. In Afghanistan, as in Iraq, more troops do not guarantee victory. The Brits doubled up their military engagement in Helmand province and since then the situation has only worsened. For all the talk of rebuilding the country, the only Americans or NATO soldiers that typical Afghans outside Kabul encounter are the ones that eradicate their year-long harvest of poppy crop or fly the planes that wipe out entire families of innocent civilians along with militants. As in the Cold War, containment, rather than rollback or appeasement, is the better policy. Taliban control of the southern provinces will likely ebb and flow, but they cannot take over Kabul like they did in 1996.

But the real issue is Pakistan. Although not treated as such, Pakistan is the key country in the so-called war on terror. It is the second most populous Muslim country and its nuclear arsenal counts with more than 100 warheads. It is a battleground where Islamic radicalism and secular democratic forces fight daily for the heart of the country. In Pakistan, as far as the United States is concerned, less is more. When the United States invaded Afghanistan in 2001, the Islamists were the direct beneficiaries in the following elections, gaining twice as many votes as they previously had and catapulting them into positions of power in the North West Province and Baluchistan. As General Musharraf struggles to handle multiple challenges to his rule, from both secular and religious forces, and Pakistan toys with democracy in moments of uncertainty, it is not difficult to imagine how tough talk of US intervention would strengthen the Islamists and more radical groups over the secular forces expected to group around Benazir Bhutto. It seems like an awful price to pay for a few terrorists on the loose.

Tuesday, July 31, 2007

The Impact of Incarceration

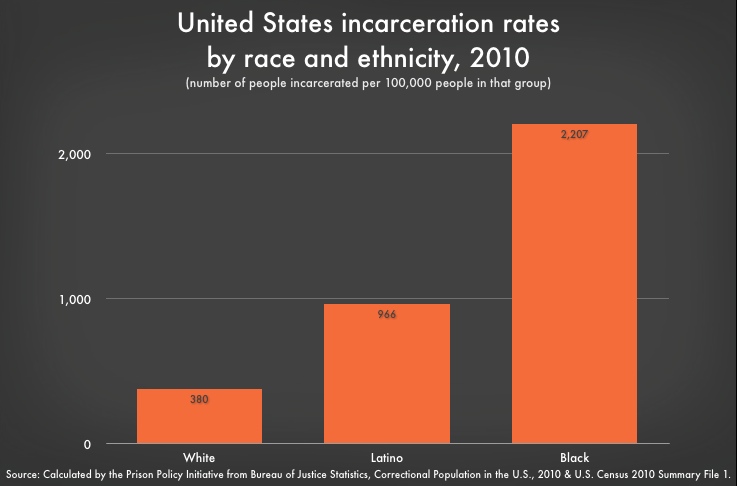

The U.S. has the highest rate of incarceration in the world. Incarceration patterns are particularly skewed toward African Americans, as evidenced in the graph below from the Prison Policy Initiative.

Lots of experts and commentators focus on either the necessity or injustice of US penal policy, but relatively few look at its repercussions outside of moral issues of racial imbalance and the skyrocketing costs of incarceration. Though some of us no doubt intuit the potential negative effects of incarcerating a huge chunk of certain communities, there's not that much (though there is some) work done on figuring out the 'trickle down' impact of incarceration.

That being said, I stumbled across a study from the University of Wisconsin which really gets one thinking about how criminal justice policies feeds into the web of socioeconomic issues. Specifically, the authors asked what impact black incarceration had on black families, and even more specifically, on child poverty. Here's what they found:

- It appears that the main effects of imprisonment on child poverty occur not through removing men from communities, but from returning them to communities with diminished earning capacity.

- The effects of imprisonment vary with class. High imprisonment rates have less impact on children with college-educated mothers, and appear to be associated with higher rates of marriage for college-educated mothers.

- The effect of imprisonment on child poverty is always positive, although it is not necessarily large enough to be significant for all educational groups.

- High rates of Black male imprisonment are associated – after several years' lag – with reduced family income, especially in less educated families with men in them.

Still, you have to admire the effort. The closer we get to unraveling the concentration of difficulties that hampers low-income families, the better off we'll be.

Monday, July 30, 2007

Health Savings Accounts: Thoughts & Problems

So what's the deal with HSAs? According to a Treasury Department information sheet, HSAs are accounts that "you can put money into to save for future medical expenses." There are, of course, more to them than just that.

First up, HSAs are supposedly tax friendly, providing "triple tax savings" by giving account holders tax deductions when they contribute to their accounts, allowing for tax-free investments with HSA funds, and tax-free withdrawals for qualified medical expenses. Second, they are portable in the sense that, like a 401k, you can take an HSA with you from job-to-job, state-to-state, etc.

HSAs are only available for people who participate in a High Deductible Health Plan (HDHP). An HDHP is a plan with low premiums (i.e. you don't pay a lot for health coverage) and high deductibles (i.e. you pay a lot out-of-pocket, up front, for medical services).

A lot of folks, particularly conservatives, like HDHP's because, as the Commonwealth Fund succicntly notes, they allegedly (a) lower health care costs by causing patients to be more cost-conscious, and (b) make insurance premiums more affordable for the uninsured. You can why, in theory, this might make sense: if you have to pay more out-of-pocket you will be more wary of spending money on health matters, and if the basic 'membership fee' (i.e. the premium, i.e. what you need to pay to get basic coverage) is low, then more people can afford it.

The problem with the logic behind HDHPs, of course, is that if you don't have the cash on hand to pay deductibles, you have trouble getting access to care. In theory, HSAs are supposed to help you with this, by helping you save for health care when you need it. But studies (from places like the Kaiser Foundation to Families USA) have cast some doubt on this potentiality, particularly for low-income families.

First off, low-income families will not benefit from the tax breaks built into HSAs, because the tax deductions come from income taxes. Income tax is progressive: the more money you make, the bigger the tax rate. Thus, the tax breaks of HSAs associated with income--like tax-free investment and tax deductions for money put in the account--will greatly benefit the rich, and not so much the poor.

Second, as I've made mention in other blog posts, low-income households only have a limited amount of funds to spend outside of current expenditures. A reliance on high-deductible plans essentially presupposes that HSAs will allow everyone to be rich enough to cut-back on readily available funds for cost-of-living expenditures. This is no guarantee by any means, particularly given disparities in start-off wealth among socioeconomic groups and the skewed distribution of financial literacy. HSAs could end up preserving--if not exacerbating--existing inequalities.

Third, the goal of cost-consciousness is a risky one. If low-income families have to pay a bigger percentage of their entire pool of funds for out-of-pocket expenses, they might be less inclined to get health are for any reason, no matter how serious. Traditional insurance schemes pool the healthy and the unhealthy together, in order to dilute the cost of care. But with HSAs, the unhealthy may become too expensive to be effectively ensured.

This is problematic: health is positively correlated with socioeconomic status. A number of social factors, such as wealth and education, are strongly associated with health. This is also true for older Americans. Thus in a broad sense, the people who would benefit the least from HSAs need them the most.

Ultimately, HSAs--at least in their current form--just don't cut it.

Friday, July 27, 2007

The Road to the Promised Land: Universal Health Care at an Affordable Cost

When the Wisconsin State Senate proposed provisions for a universal health care plan in their budget, many progressive groups applauded their effort and pointed to this legislation as the first step toward providing quality health insurance for all Americans. However, as your newspaper points out (“Cheese Headcases,” July 23), the Wisconsin State Senate’s plan includes tax increases that could easily drive skilled workers and profitable business from the state of Wisconsin. Skepticism in the government’s ability to lower costs of healthcare by centralizing administrative costs is understandable—both the federal and state governments have shown an inability to control costs, find the best price and the lowest bidder, and directly stimulate market growth. But we cannot dismiss the idea of universal healthcare because of the Wisconsin state legislature’s lawmaking.

On May 1st of this year, students from the Wisconsin chapter of the Roosevelt Institution, a student-run think-tank with 7,000 members around the country, presented viable healthcare legislation to the Wisconsin Assembly’s Committee on Aging and Long Term Care. Our plan aimed to provide care to every Wisconsin citizen while lowering insurance costs with as little government intervention as possible. We made our presentation while the Wisconsin State Legislature was developing their budget, and although they found a healthcare plan in the Democrats’ work, it wasn’t quite what we had in mind.

The policy concept was born out of pragmatism and efficiency, not ideology, and it kept the insurance industry structure intact. Using market-based solutions to address some of the issues that currently plague Wisconsin’s system, we outlined a three-pronged approach.

The first goal was to lower the enormous healthcare costs faced by senior citizens. We proposed creating Health Savings Accounts (HSA) to which both individuals and businesses could contribute tax-free funds. Their HSAs are similar to the common 401(k), but if the income generated from the growth of an HSA is exclusively used to finance medical expenses, then it is tax-free as well.

The second goal was to lower the number of uninsured citizens in Wisconsin. The original plan avoided the inclusion of any provision mandating that every resident of the State of Wisconsin be insured, it quickly became obvious that this provision was necessary. While the poor and uninsured may not get adequate preventive care, the current Wisconsin system makes sure that they get medical attention when they truly needed it. But, according to estimates in a 2003 Kiser Foundation study, when an uninsured individual receives medical attention, American taxpayers pick up almost three-fifths of the tab. Mandating that everyone obtain health insurance not only improves the well-being of many citizens, but it also saves a significant amount of government money.

The final goal was to subsidize care through vouchers for private insurance. Many people are too rich to qualify for current government programs, but too poor to afford coverage themselves, and current legislation does nothing to address this grievous error. Targeted subsidies both keep the bill from becoming a new burden to the States already stressed budget, while helping those who truly cannot afford coverage. The State Senators' plan does quite the opposite, by creating a pricy program that reverts some of the progress made by Wisconsin’s innovative welfare reform of the late 1990s. Our plan for subsidy provides affordable coverage for every Wisconsin citizen. (not everyone!)

Our proposal also reduced bureaucracy in healthcare. Their market-orientated approach was far more effective—both in terms of cost and quality of care.

The Wisconsin Democrats’ plan is one of outrageously high tax increases and more bureaucracy. Our plan was one of efficiency and efficacy.

We must remember that government bureaucracy and inefficiency is no reason to malign a policy idea like universal healthcare outright. Sound and efficient ideas to help Americans, ideas like the one proposed by these students, should always be considered in their purest forms. Just because a budget that proposes universal healthcare has damaging effects doesn’t mean that universal healthcare is a bad idea.

Our proposal to fix a flawed healthcare system on a localized level is exactly the type of pragmatic solution that should not be adulterated by partisan ideology. Failed legislation in this capacity is nothing less than a destructive force in the social welfare of American citizens.

Wednesday, July 25, 2007

Spending, Saving, and Social Policy

For the poorest Americans, expenditures exceed income. Check out this graph to the left I slapped together form the Consumer Expenditure Survey (CES). You'll note that it's not until you get into the middle quintile of income earners that income exceeds expenditures. For the bottom 40 percent of America, spendings outstrip income.

On its face, this suggests that poor Americans really don't have room to save. But, as I've noted, these expenditure measures include everything from shelter to cigarettes, meaning that there is some wiggle room to work with. Here I want to address the relationship between this wiggle room (i.e. non-essential expenditures that can be cut back to induce saving) and the graph above.

Let's take a collection of categories from the CES as our 'expendables': alcohol, smoking/tobacco, entertainment, and personal care products. We'll treat alcohol and smoking/tobacco as completely expendable, and the other two as only partially so (no one can reasonably go without entertainment or personal care). So let's say the average household in the bottom two quintiles cuts its spending in these areas by half. Over one year, eliminating booze/smokes and 50 percent of entertainment/personal care would save the lowest quintile $1,006; the second lowest would save $1,441.50 with the same cutbacks.

Of course, there are some significant caveats that dilute this scheme. Firstly, at least some of the households in CES were families (the average number of people in households for the bottom two quintiles hovered around two), meaning that expenditure cutbacks aren't always so easy, particularly with regards to personal care and entertainment (i.e. stuff kids need/want). Second, the $1,006 and $1,441.50 in savings do not make up the difference between income and expenditures represented in the graph above for the average household in these income brackets.

But before we close the book we need to look at two variables: the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Individual Development Accounts (IDAs). A qualified head of household with one qualifying child who brought in the reported CES income of the lowest quintile ($9,626) would be $2,740 in 2006. For the second quintile ($25,546) it would be $1,030. If this same individual had two kids, (s)he would bring in $3,870 (lowest income quintile) or $2,270 (second lowest quintile) from the EITC.

So as it stands, a head of household who cuts spending in the ways discussed here and qualifies for the EITC already has somewhere between $3,746 and $4,876 (if in lowest quintile) or $2,471.50 and $3,276 (if in second lowest). Now, what if this earner was to put this amount of savings in an IDA?

The usual match rates for IDAs are 2:1, meaning that for every dollar deposited by the account-holder, 2 are deposited by the matching bodies. Most IDA programs are built to last from 1 to 3 years, and some often are only matched up to a certain amount (e.g. $500). If we play it safe and take a 1 year IDA program with a 2:1 match rate and a max matching scheme of $500, this means that over the course of a year, we can in essence tack on an extra $1,000.

So now we have between $4,746 and $5,876 (if in lowest quintile) or $3,471.50 and $4,276 (if in second lowest) in saved funds. These amounts don't help the poorest quintile break even, but they do in fact make it possible for the second quintile to bridge the gap between income and expenditures in the graph above.

The message should be clear: helping working families is a patchwork pursuit that needs to be fought on multiple fronts. There's an important role for individual decision-making and personal responsibility as well as for creative social policies that feed into one another and help 'snowball' assets and well-being. The more we view poverty as a one-dimensional social condition, the more we tie our hands; the more we focus on viewing low-income individuals as active participants in their own life--in addition to being a policy-relevant population--the more we might see some progess.